The company in this case, which we’re calling ‘Acme Gas Company,’ followed a competency management system (CMS) project in three phases initially:

- Phase I: development of philosophy and strategy and all the processes and documentation needed to implement the program

- Phase II: delivery of training, followed by performance assessments by qualified assessors in the workplace

- Phase III: assessments of all operations leadership

After Acme management assigned a project manager with a background in CMS implementation, the CMS manager assembled a team, which included all the new leadership members with the responsibility to operate and manage this new plant through and after startup. They began to establish the requirements and set out a timeline for key milestones to be in place to assure they could meet the startup date.

In line with the project program plan, the team first developed a philosophy and strategy for staff development and their ability to demonstrate competence for each of their given job roles. Their philosophy outlined that each technician’s and operations leader’s role would have a job-specific competency standard that would clearly define the knowledge and performance requirements for each. As part of this program, they planned to hire new ‘green’ technicians with only a two-year degree and no experience working in a gas plant environment. The philosophy behind this was to train/develop these first-time technicians in the ‘Acme Way.’

This was done with a hope to create a younger, highly-capable demographic for Acme given their average worker’s age was over 55. It was also hoped these young technicians fresh out of school would develop a loyalty to the company given the data from the Deloitte 2016 Millennial Survey showed the lack of commitment by millennials to a given job role, where on average, 66% leave their jobs between year 1 and 2, and years 2 and 5. The same survey noted there was more that played into Millennials sticking with a given job, mainly, who they reported to. As Dr. Gustavo notes, “Millennials are not job hoppers, rather they are boss shoppers.” Where most organizations fail is in their neglect of developing competent operations leadership. Jim Wetherbee states the following: “Leaders must clearly set expectations to follow the company guidance, including what practices are to be used. Practices are the ways of working, including the methods for making decisions or performing tasks. Employees are expected to conform to the standards and principles, and comply with the policies and rules. Employees must understand and accept their accountability—by committing to perform. If the accountability is not accepted, the leader should not expect performance. When organizations fail, this is often the omitted step; the leaders may provide the policies and rules, but then they fail to set expectations to follow certain practices, won’t test for understanding or ask for commitment, and don’t verify that the expected practices are actually being performed.”

So, part of the leadership development and demonstration of their competency was around effective management of their next-generation workforce. Here is how the program was broken down: there were six technician and five leadership roles that would make up the plant team once it went into full production. Here is a list of each role:

Technicians:

- Unit Operator

- Control Room Operator

- Instrumentation Technician

- Automation Technician

- Electrical Technician

- Mechanic Technician

Operation Leaders:

- Plant Manager

- Operations Manager

- Plant Supervisors

- Maintenance Supervisors

- HSE Leads

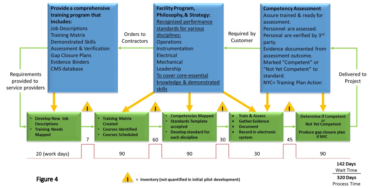

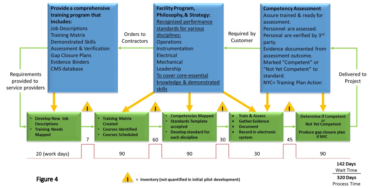

Within their strategy they determined to create and put in place a comprehensive training program. The program included the following outline:

- Revise/Update Job Descriptions for each role

- Create a training matrix to fit the plant/equipment

- Define criteria to demonstrate performance skills

- Define methods of assessment of skills

- Verification methods for qualified assessors

- Develop Skills Gap Closure Plans

- Assemble Evidence Binders

- Implement eAdmin Software Tool to support CMS

When the philosophy and strategy was agreed and signed off, requirements were sent out to process and service providers to bid. Once providers were vetted and approved, they started the buildout of their program. During the bidding process to bring in a CMS-type service company to help build this program with them, the Acme project manager rejected the initial three bids. The team was discovering that, due to U.S. industries focusing so much on training vs competency performance, these proposals were all mainly centered on training with only knowledge-type assessments. Additionally, the cost and time in the proposals were outside the scope of what their budget and project would allow. They resubmitted their bidding scope back out to the market, costing them time, but did secure a company that met their requirements.

During the bidding process, part of the team started reviewing their in-house job descriptions. They found that some job descriptions didn’t exist within their segment of the company and the ones that did, lacked clearly defined duties and responsibilities. They made a request from the other segments within the company to send their similar job descriptions. It was decided to form a single document template for all job descriptions, using what was available in the current job descriptions, and building out the missing sections.

Another part of the team started a training needs assessment based on the processes and equipment in the plant design for each job role. This proved to be a larger-than-expected undertaking. One finding was the lack of one single source provider with a full library of online training materials to support the project. It was then decided to submit to the senior management for a change of scope to have an eTraining provider create a custom online training package specific to the new facility. The new scope was approved and a provider selected to start this development. Note: This caused a delay in the actual training schedule for the operations technicians who were hired for the new facility. The training matrix was completed and external courses identified for the trade technicians (Instrument, etc.), so their training was able to start on time.

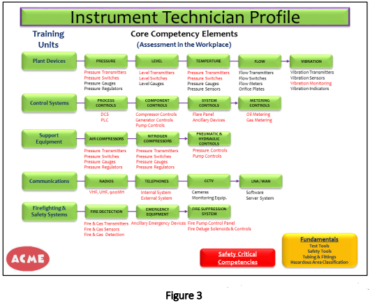

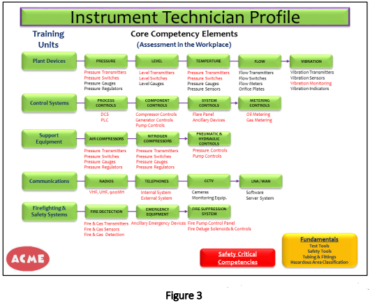

Process mapping analysis was started with the leads in each job role identified to capture each task/activity required of an individual within their job role. This created the foundation for each competency that would form the competency profile within the job descriptions.

As part of this process, a risk matrix was used by this team to determine which competencies were safety critical vs those that were non-safety critical. Once the profiles were signed off by the leadership, the development for each competency standard started.

As each standard was developed using the lean Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA) cycle, the final sign-off came from the chief engineers for the different disciplines. Once they put their stamp on each standard, it was then signed off by the company’s legal department. Once management signed off and took ownership, assessment guide development began for each standard. It was determined that the assessment guides would form the tool needed by the qualified competency assessors to conduct and document each assessment. Each assessment guide mirrored the knowledge and performance requirements/criteria directly from the job competency standards. The knowledge questions and performance range statements were then created, which the assessors were required to follow during the assessments. This allowed an objective process for equally measuring each individual during the assessment process. As part of the strategy, it was determined to initially use third-party trained and qualified assessors. As laid out in the Acme CMS strategy, each third-party assessor was verified by Acme using a standardized form to measure the assessor’s competence for the knowledge needed to conduct the assessments. The assessors were instructed to follow the assessment guide to the letter and avoid personal opinions or judgments when conducting and documenting all assessments.

As the competency standards and assessment guides were under development, the new hires started their prescribed training programs for their given job roles. A change management program was also being developed for roll out to management, operations leadership, and the frontline technicians. The CMS program was a new program and process for Acme, so communications was key to having the right message get out across the operations organization.

As part of the program, each technician was provided an evidence binder that included:

- A letter from the senior manager explaining why they were implementing a CMS program and his support of the program.

- A copy of their new job description.

- A copy of their personal competency profile, which was a one-page graphic that listed all the competencies for their job role, identifying which were safety critical.

- A copy of the process task maps showing the breakdown of each task/activity for each competency.

- A copy of their job role competency standard, which spelled out in detail the knowledge and performance requirements.

- A section to place hard copies of documented evidence where they completed task/activities. This would be reviewed by the assessor during the actual site assessments and documented in the assessment summaries on the assessment guides if valid and authentic for an individual.

A CMS eAdmin software solution was selected and purchased and an admin hired to gather and capture all the documentation developed for the CMS program as well as all the completed assessment guides into this new database.

Once each of the third-party assessors were approved and verified, the assessment process was started in earnest with the technician staff. Given that each technician had received a copy of their competency standard for review, it was observed that a majority of them had not reviewed their standard prior to the initial assessments. We’ll also note that once the assessment process started, that word spread quickly through the teams and the assessors saw an increase in technicians who were better prepared with a better understanding of their standard requirements. We’ve provided testimonies from three individuals who underwent assessment. You’ll see that most were reluctant to undergo the assessment process initially, because they worried that it could result in the loss of their job. So even with the communications rollout, it was clear that, in the future, more and continual communication needed to come from all levels of leadership to help provide assurance that this program is about risk management and not about releasing an individual from their job. Communications should show the investment a company is making in their people when putting a CMS in place.

The Assessment Process

Phase II of the CMS program was focused on scheduling and conducting the assessments with third-party-qualified and Acme-approved assessors for each job role. The assessments started during the commissioning of the plant equipment once the technicians had spent time with the equipment manufacturing representatives working around the equipment in the different units. The P&ID drawings were in place, but the operating procedures were behind schedule. The plan had been to use the procedures during the assessment process to help the technicians validate them, but this did not occur.

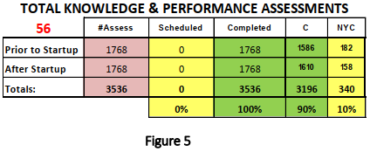

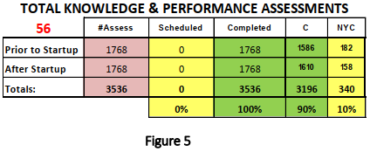

There were 56 total technicians across the difference job roles listed previously. So, based on the competencies listed across the profiles for each technician, a total of 1,768 required assessments were initially scheduled. These assessments focused only on the Knowledge section of the competency standards for each technician and were scheduled prior to startup of the new facility. It was decided by the leadership team that the performance assessments would be delayed until the plant was in full operational mode and running with minor upsets. It was thought that this would give the technicians a better understanding of how the plant runs, even though most of the technicians had worked with the same type of equipment and systems in previous job roles. This required an additional 1,768 performance assessments.

After the plant had been running for several months and lining out, the third-party assessors were brought back to conduct the performance assessments. These assessments were conducted within the plant units around the equipment while it was operating. Observations were made by the assessors as the technicians conducted work; they walked down the process system piping and components for the assessors and were followed up with limited questioning based on range statements listed from the performance sections of competency standards for each individual competency in the assessment guide. The assessors reviewed any performance evidence documentation the technician had added to their evidence binder to see if it could be applied to the assessments to help show demonstrated competence, and if it was valid and authentic to the individual, then this was included in the assessment summary. At this point it was noted by the assessors that all the technicians appeared to have reviewed their competency standard and were fully engaged with the assessment process. During the assessment summary feedback sessions between the assessor, the technician, and their direct supervisor, the technicians stated how they were learning more about the plant and processes due to having this program in place and had a positive view of the Acme CMS program overall.

ACME’S RESULTS

So, in summary of the Phase I & II CMS program (Ref. figure 4), the following provides the team’s analysis, key statements and timeline:

Previous State:

- The operations leaders for the project had no clear understanding of where the skills gaps were for each technician hired for the new facility.

- They had a limited budget to build a robust program and initial bids came in at higher than expected cost.

- There was almost no buy-in by the senior management, who weren’t convinced putting a CMS in place was necessary. The one factor that allowed this project to move forward was the trust in the senior operations project manager along with his track record within the organization. Although the project didn’t get the level of funding it needed, the operations project manager and his team were innovative in some areas to ensure the integrity and robustness of the program.

- Findings from incident root cause and audits showed lack of demonstrated competency by the current workforce at other facilities.

- There was no standardized approach within company to assure and maintain the level of skilled performance needed to support the safety and reliability of operations, while losing a large percentage of senior capable operations staff to retirement globally.

Following CMS Implementation – What Was Learned:

- The creation of the custom site training matrix used up resources that could have been better used in other areas. The team recommended to the leadership starting with a generic training matrix in the future and adding plant specifics, which would help create a more standardized process across the whole organization.

- The creation of custom job descriptions also used up resources much longer than expected. The team recommended the same as with the training matrix: agree on a standard generic template and add specifics after. Competency performance standards were built for all disciplines and were verified by chief engineers and signed-off by the legal team.

- CMS software should have been adopted earlier, with user training to input all documentation.

- The process of using third-party competency assessors worked well and provided a truly independent view of skills gaps discovered in the assessment process.

- With Acme’s investment in the CMS for this new project, it helped them gain the ability to easily modify documentation and adopted a CMS program for other facilities within the organization with shorter ramp-up time and implementation cost.

- Acme has fundamentally seen the following outcomes from the CMS program:

- Safety of the workforce has increased and TRIR has started to drop.

- Reporting shows less environmental incidents, which contributes to the communities where they operate.

- The equipment is showing less downtime, greater mechanical integrity, and higher reliability of the equipment and systems.

- Costs have been optimized while employee talent is being developed by focusing on defined skills gaps from assessments outcomes.

- Acme now has the ability to replicate a proven model at any site with minimal resources and cost.

So out of the total assessments conducted on knowledge and performance, the data recorded showed a 10% skills gap across the 56 technicians.

Job position wise, skills gaps were broken down in the following percentage:

Mechanical Technicians = 10 NYCs or 10%

Electrical Technicians = 25 NYCs or 14%

Inst/Auto Technicians = 34 NYCs or 28%

Operation Technicians = 219 NYCs or 29%

Control Room Technicians = 46 NYCs or 8%

These were the base line assessments, completed over a six-month period for the new facility. As part of Acme’s ongoing operational CMS strategy, performance assessments will remain a part of the facility program, with reassessments every 3 and 5 years based on their safety critical equipment and competencies. The focus of these assessments will be on what has changed within operations since the individual’s last assessments.

The leadership assessments were part of Acme’s CMS Phase III. Leadership competency standards were developed and approved. Each leader was assessed by a leadership assessor panel, made up of 2–3 qualified leadership assessors. The assessors only asked questions from the approval assessment guides to ensure fair and consistent coverage from the standards. Knowledge assessments were conducted offsite to prevent interruptions from daily operational matters. After each of the leaders had finish these assessments, then the assessor panel observed each leader individually in their workplace during live operations, asking any follow-up questions from the assessment guide. Like the technicians, it was noted that the leaders had paid very little attention to their competency standard prior to their initial assessments. Word spread through the leadership ranks and it became obvious that the later scheduled leaders had reviewed the requirements in their competency standard prior to their assessment. Out of the 27 leaders, only one was found to have NYCs against his standard. A development plan was put in place and once he was ready, he stood for reassessment. The assessment showed he was now able to meet the requirements of the leadership standard for his role, having closed the initial gaps in his baseline assessment. As of this publication, 90% of the plant leadership has been fully assessed and the remaining individuals are scheduled to be completed by end of 3Q this year.